Big Bang Thought of the Day by Nobel Laureate Peter Higgs, “The Big Bang made the universe explode into existence. The Higgs boson made it stay.” In July 2012, scientists at CERN announced a discovery that answered one of the most fundamental questions in physics: why does anything in the universe have mass at all? The answer came in the form of a subatomic particle weighing about 125 gigaelectronvolts (GeV), detected after analyzing data from more than one quadrillion proton–proton collisions inside the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). That particle was the Higgs boson.

The discovery did more than confirm a theoretical prediction. It stabilized modern cosmology. Without the Higgs mechanism, particles created in the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago would have traveled at the speed of light. Atoms would never have formed. Galaxies would not exist. Stars, planets, and life would be physically impossible.

This is why physicists describe the Higgs boson as the particle that allowed the universe to settle after its violent birth. The Big Bang explains how space, time, and energy emerged. The Higgs field explains how that energy condensed into structured matter. Together, they form the backbone of the Standard Model of particle physics, the most successful scientific framework ever built to describe reality at its smallest scales.

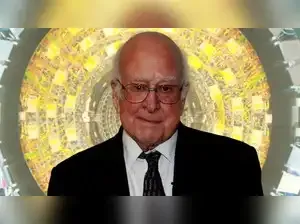

Peter Higgs, the British theoretical physicist who first proposed the idea in 1964, lived long enough to see his theory confirmed and honored with the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics. His work quietly resolved decades of competing universe theories, many of which failed because they could not explain mass without breaking fundamental laws of physics.

Peter Higgs, working at the University of Edinburgh, proposed a radical solution. Instead of particles being born with mass, he suggested that mass arises through interaction with an invisible field that fills all of space. This field would slow some particles down, much like movement through a viscous medium, effectively giving them inertia. Others, such as photons, would pass through untouched and remain massless.

The idea was mathematically developed alongside similar work by François Englert, Robert Brout, and others. What made Higgs’ contribution distinct was his prediction of a new particle—a detectable quantum excitation of the field itself. This became known as the Higgs boson.

At the time, the proposal was controversial. No experiment on Earth had the energy needed to test it. For decades, the Higgs remained an elegant theory without proof, even as alternative ideas—such as technicolor and composite models—rose and fell.

As the universe cooled below a critical temperature—about 10¹⁵ Kelvin—symmetry broke. This is where the Higgs field became active. Its value shifted from zero to a constant nonzero level across space. This transition gave mass to elementary particles through their coupling to the field.

This moment was decisive. Particles with mass could now slow down, combine, and form stable structures. Quarks bound into protons and neutrons. Electrons attached to nuclei. Within 380,000 years, neutral atoms formed, allowing light to travel freely. This event is still visible today as the cosmic microwave background, measured with extreme precision by satellites such as Planck.

Without the Higgs mechanism activating shortly after the Big Bang, none of this sequence would occur. Competing cosmological theories failed precisely here. They could describe expansion, but not stabilization. They could model energy, but not matter.

Between 2010 and 2012, two major experiments—ATLAS and CMS—independently searched for Higgs signatures. They looked for specific decay patterns predicted by theory, including decays into two photons, four leptons, and pairs of W or Z bosons.

On July 4, 2012, CERN announced a new particle detected with a statistical confidence of 5 sigma, the gold standard in physics. Its mass, decay channels, and behavior matched Higgs predictions with remarkable accuracy.

By 2013, Peter Higgs and François Englert were awarded the Nobel Prize. Higgs later remarked that he never expected to see experimental confirmation in his lifetime.

The discovery eliminated major alternative models and cemented the Standard Model as experimentally complete—though not final.

Physicists are now studying whether the Higgs boson interacts with dark matter, which makes up about 27% of the universe’s total energy density. So far, no deviation from Standard Model predictions has been confirmed, but upgraded LHC runs continue to collect data.

The Higgs also plays a role in unifying gravity with quantum mechanics. Any future theory of everything must incorporate the Higgs field naturally. Without it, modern cosmology collapses.

Peter Higgs often resisted the nickname “God Particle,” calling it misleading. Yet his work answered a question as old as science itself: why does the universe have substance instead of pure light? The Big Bang created space and energy. The Higgs boson gave that universe weight, structure, and permanence.

In doing so, it settled one of the longest-running debates in theoretical physics—and made existence itself possible.

In 2012, CERN confirmed a particle with a mass of about 125 GeV after analyzing over one quadrillion collisions. The Higgs boson explains how fundamental particles acquire mass through the Higgs field. The “God Particle” nickname reflects its importance, not any religious meaning.

2: How does the Higgs boson relate to the Big Bang theory?

The Big Bang occurred 13.8 billion years ago, creating energy without structure. When the universe cooled, the Higgs field activated within the first second. This process gave particles mass, allowing atoms, stars, and galaxies to form instead of dispersing as pure energy.

3: Why did the Higgs boson discovery matter to modern physics?

Before 2012, the Standard Model was incomplete. The Higgs discovery confirmed the mechanism that preserves gauge symmetry while explaining mass. It eliminated rival theories that failed experimental tests and validated decades of precision measurements across particle physics.

4: What unanswered questions remain after the Higgs boson discovery?

Despite confirmation, 95% of the universe remains unexplained as dark matter and dark energy. Current data shows no Higgs interaction with dark matter particles. Ongoing LHC upgrades aim to detect deviations that could reveal physics beyond the Standard Model.

The discovery did more than confirm a theoretical prediction. It stabilized modern cosmology. Without the Higgs mechanism, particles created in the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago would have traveled at the speed of light. Atoms would never have formed. Galaxies would not exist. Stars, planets, and life would be physically impossible.

This is why physicists describe the Higgs boson as the particle that allowed the universe to settle after its violent birth. The Big Bang explains how space, time, and energy emerged. The Higgs field explains how that energy condensed into structured matter. Together, they form the backbone of the Standard Model of particle physics, the most successful scientific framework ever built to describe reality at its smallest scales.

Peter Higgs, the British theoretical physicist who first proposed the idea in 1964, lived long enough to see his theory confirmed and honored with the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics. His work quietly resolved decades of competing universe theories, many of which failed because they could not explain mass without breaking fundamental laws of physics.

Peter Higgs and the mass problem that threatened modern physics

By the early 1960s, physicists faced a deep contradiction. Quantum field theory predicted that fundamental particles should be massless. Yet experiments showed that particles such as W and Z bosons, which mediate the weak nuclear force, clearly had mass. Adding mass directly into equations destroyed a core principle called gauge symmetry, which underpins both electromagnetism and nuclear forces.Peter Higgs, working at the University of Edinburgh, proposed a radical solution. Instead of particles being born with mass, he suggested that mass arises through interaction with an invisible field that fills all of space. This field would slow some particles down, much like movement through a viscous medium, effectively giving them inertia. Others, such as photons, would pass through untouched and remain massless.

The idea was mathematically developed alongside similar work by François Englert, Robert Brout, and others. What made Higgs’ contribution distinct was his prediction of a new particle—a detectable quantum excitation of the field itself. This became known as the Higgs boson.

At the time, the proposal was controversial. No experiment on Earth had the energy needed to test it. For decades, the Higgs remained an elegant theory without proof, even as alternative ideas—such as technicolor and composite models—rose and fell.

The Big Bang, cosmic inflation, and why mass had to emerge quickly

The Big Bang theory describes an early universe that was unimaginably hot and dense. Within the first 10⁻³⁶ seconds, the universe underwent rapid expansion, known as cosmic inflation. During this phase, all particles behaved as if they were massless.As the universe cooled below a critical temperature—about 10¹⁵ Kelvin—symmetry broke. This is where the Higgs field became active. Its value shifted from zero to a constant nonzero level across space. This transition gave mass to elementary particles through their coupling to the field.

This moment was decisive. Particles with mass could now slow down, combine, and form stable structures. Quarks bound into protons and neutrons. Electrons attached to nuclei. Within 380,000 years, neutral atoms formed, allowing light to travel freely. This event is still visible today as the cosmic microwave background, measured with extreme precision by satellites such as Planck.

Without the Higgs mechanism activating shortly after the Big Bang, none of this sequence would occur. Competing cosmological theories failed precisely here. They could describe expansion, but not stabilization. They could model energy, but not matter.

CERN, the Large Hadron Collider, and the 2012 discovery that changed science

To test the Higgs theory, scientists needed unprecedented energy levels. The Large Hadron Collider, a 27-kilometer underground ring straddling the French–Swiss border, was built for this purpose. Costing roughly $9 billion, it accelerates protons to 99.9999991% the speed of light.Between 2010 and 2012, two major experiments—ATLAS and CMS—independently searched for Higgs signatures. They looked for specific decay patterns predicted by theory, including decays into two photons, four leptons, and pairs of W or Z bosons.

On July 4, 2012, CERN announced a new particle detected with a statistical confidence of 5 sigma, the gold standard in physics. Its mass, decay channels, and behavior matched Higgs predictions with remarkable accuracy.

By 2013, Peter Higgs and François Englert were awarded the Nobel Prize. Higgs later remarked that he never expected to see experimental confirmation in his lifetime.

The discovery eliminated major alternative models and cemented the Standard Model as experimentally complete—though not final.

Why the Higgs boson still matters for the future of cosmology

While the Higgs boson solved the mass problem, it also opened new questions. Measurements suggest that the Higgs field may place the universe in a metastable state, meaning our cosmic vacuum could, in theory, decay over extremely long timescales. This has implications for dark energy, vacuum stability, and the ultimate fate of the universe.Physicists are now studying whether the Higgs boson interacts with dark matter, which makes up about 27% of the universe’s total energy density. So far, no deviation from Standard Model predictions has been confirmed, but upgraded LHC runs continue to collect data.

The Higgs also plays a role in unifying gravity with quantum mechanics. Any future theory of everything must incorporate the Higgs field naturally. Without it, modern cosmology collapses.

Peter Higgs often resisted the nickname “God Particle,” calling it misleading. Yet his work answered a question as old as science itself: why does the universe have substance instead of pure light? The Big Bang created space and energy. The Higgs boson gave that universe weight, structure, and permanence.

In doing so, it settled one of the longest-running debates in theoretical physics—and made existence itself possible.

FAQs:

1: What is the Higgs boson and why is it called the “God Particle”?In 2012, CERN confirmed a particle with a mass of about 125 GeV after analyzing over one quadrillion collisions. The Higgs boson explains how fundamental particles acquire mass through the Higgs field. The “God Particle” nickname reflects its importance, not any religious meaning.

2: How does the Higgs boson relate to the Big Bang theory?

The Big Bang occurred 13.8 billion years ago, creating energy without structure. When the universe cooled, the Higgs field activated within the first second. This process gave particles mass, allowing atoms, stars, and galaxies to form instead of dispersing as pure energy.

3: Why did the Higgs boson discovery matter to modern physics?

Before 2012, the Standard Model was incomplete. The Higgs discovery confirmed the mechanism that preserves gauge symmetry while explaining mass. It eliminated rival theories that failed experimental tests and validated decades of precision measurements across particle physics.

4: What unanswered questions remain after the Higgs boson discovery?

Despite confirmation, 95% of the universe remains unexplained as dark matter and dark energy. Current data shows no Higgs interaction with dark matter particles. Ongoing LHC upgrades aim to detect deviations that could reveal physics beyond the Standard Model.